Before the days of the Internet, advertisers and marketers would target their target audience by showing their ads on TV at certain times of the day, publishing their ads in newspapers that their audience read, and putting up billboards in places where their audience would see it.

Nowadays, advertisers and marketers can tap into the online world and take massive amounts of user data to help get their message in front of the right person at the right time.

And this user data is big business.

According to Forrester Research, U.S. companies spend more than $2 billion annually to tap into consumer data.

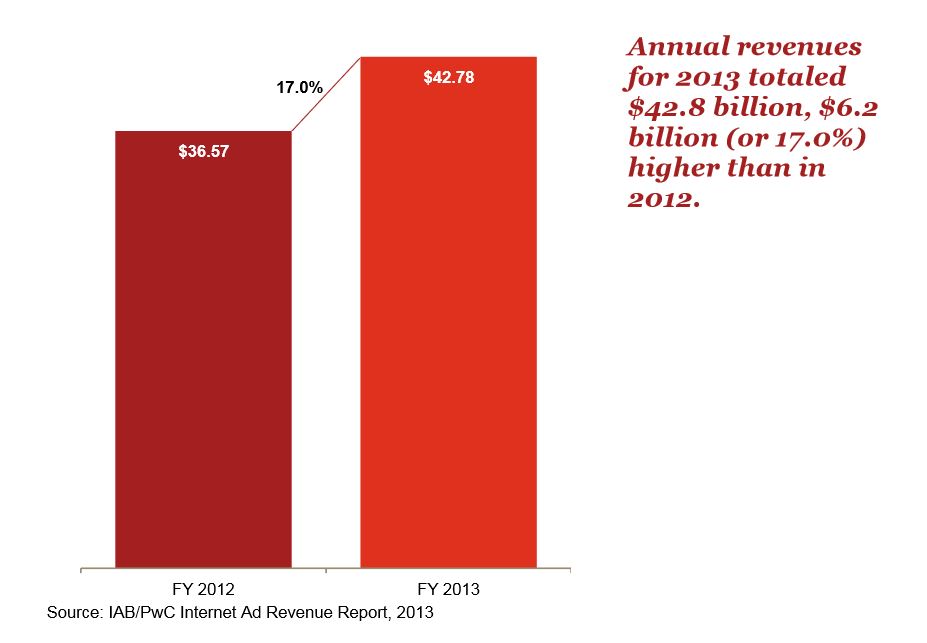

Online users are being tracked more now than ever before, and the online display advertising industry is seeing this abundance of user data translate into dollars:

But what implications does this mass of user data have on both the user and business side?

How Your Data is Collected, Shared, and Traded

Most intermediate Internet users know that their online activity is being tracked, usually via cookies, and used for advertising and marketing purposes – but that’s about all they know. A majority of these people don’t know just how much of their online data is being collected and is flowing through the online advertising ecosystem.

It’s a process that involves scripts and technology platforms, and it happens on just about every single page on the Internet.

And while all companies that operate within the online advertising industry collect data, there are some companies that make a business out of collecting and selling online consumer data. These companies are known as data brokers (sometimes as referred to as data brokers or suppliers).

What Is A Data Broker?

Data brokers aggregate user profiles obtained from publishers, combine, and segment them. Additional user information can be provided on demand to programmatic ad buying platforms.

Information offered by data brokers includes:

- User segmentsAd viewability

- Ad viewability

- Ad fraud detection

- Context information on publishers

We’ve written about what data broker are and how they operate in one of our previous post.

We Can Help You Build an AdTech Platform

Our AdTech development teams can work with you to design, build, and maintain a custom-built AdTech platform for any programmatic advertising channel.

How Do Third-Party Data Brokers Collect This Online Consumer Data?

Scripts

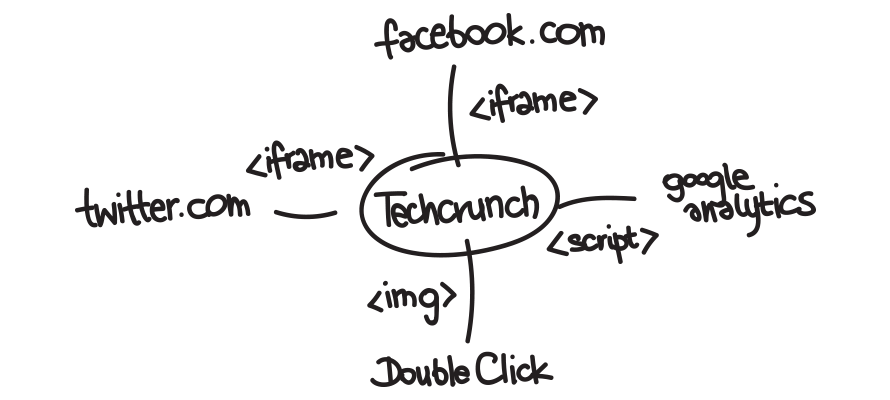

The process all starts as soon as a user accesses a website, e.g. TechCrunch, and the website starts loading content, pictures, videos, and other page elements. While all the visible elements load, the site is also loading hidden items as well called scripts (commonly known as pixels).

All websites are built using first-party scripts to present different visual elements on a webpage; however, it’s not uncommon for sites to utilize third-party scripts as well. What’s the difference? Ben Vinegar, the co-author of Third-Party Scripts, puts it nicely:

“In the strictest sense, anything served to the client that’s provided by an organization that’s not the website provider is considered to be third-party.”

There are a few types of third-party scripts and they are all responsible for performing different actions:

Ads: Used to display advertisements on a web page (e.g. banner ads).

Tracking and analytics: Used for web analytics services like Google Analytics and Piwik PRO.

Social media: Used for social widgets, such as social sharing buttons and like buttons.

Fonts: Used to display various fonts on different web browsers.

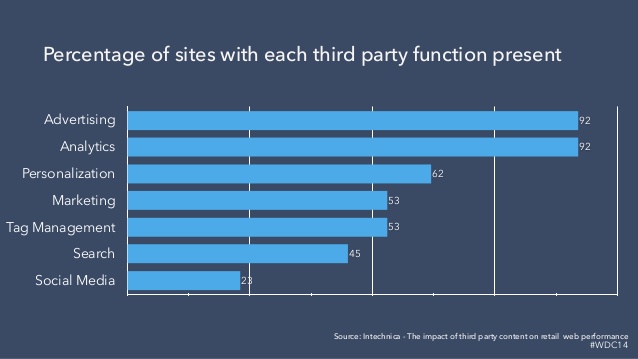

Out of all the third-party scripts, advertising and analytics scripts are the most common.

Some scripts will just execute their own actions, while others use a technique called piggybacking, which involves loading additional third-party scripts on top of the main third-party script; so for example, a social media widget may load its own script, plus other scripts and web trackers.

In addition to the points mentioned above, third-party scripts can also severely affect the performance of a website, so much so that apps and extensions are now allowing users to block these scripts from loading, therefore improving performance and decreasing page load time.

A prime example of this is the upcoming release of iOS 9. For the first time ever, the update comes with a new feature that will enable users to download an app to block trackers, ads, and other unwanted content.

For desktop devices, there is a really awesome tool for displaying the extent of third-party scripts and their properties – 3D Tilt. It’s a Firefox add-on that provides a graphical overview of the different layers of a website, including elements such as ads.

Collecting and Sharing Data

Some third-party sites are purely there to execute their intended action (e.g. display social buttons), but some are used to collect data about the website and the user. These third-party scripts are known by two names – trackers and web bugs.

Trackers are usually run by companies (data suppliers) that operate in the data collecting and selling business.

When a user accesses a website that contains trackers, information about the site and user is collected, such as:

Information about the website

- URL

- Page title

- Taxonomies (the website’s category)

- Meta data about the displayed article or product

Information about the user

- Web browser

- Enabled plugins

- Screen resolution

- Browser language

- Web history

- Geolocation

- Profile data

- Online transactional history (e.g. purchased items)

It’s important to note that data can also be shared directly between data brokers and companies, which would result in the data broker receiving different sets of user data that can’t be obtained through web trackers, such as demographic information – e.g. income, gender, age, etc.

The trackers will also search for their third-party cookie and if they are unable to find it, the trackers will generate a UUID (universally unique identifier) and save it as a third-party cookie in their domain – e.g. tracker.examplesite.com.

This third-party cookie will help the tracker identify the user on any website that loads the tracker in the future.

Once the tracker has created the third-party cookie, it can then sync the cookie with other companies in the online display advertising ecosystem, such as data-management platforms (DMPs), which make the cookie “active” and allow them to start using the collected data.

Selling the Data

Once data suppliers (the companies running the trackers) have collected this data, they usually sell it on to data brokers (e.g. DMPs) by one of two ways:

Via a revenue share model: Brokers sell data to other intermediaries in the ecosystem (e.g. DSPs, ad exchanges, ad networks, etc.) and give the supplier a share of the revenue.

The main problem with this method of payment is that the data supplier has no way of knowing when the data is sold and how much it was sold for. This is just another case of how a lack of transparency is damaging online display advertising.

Via a cookie CPM basis: Brokers sell data on a cost per mille (cost per thousand) basis, which means that the supplier is paid a fixed amount (e.g. 30 cents) for each 1,000 unique cookies created by their site(s).

Data brokers take the purchased data, process it, and then create thousands of buckets (segments), including:

- Relationship status – e.g. In a relationship

- Interests – e.g. Gardening

- Ethnicity – e.g. Native American

- Age group – e.g. 35-39

- Gender – e.g. Male

- Connected devices – e.g. XBOX 360

- Home Value – e.g. Between $200k – $400k

- Annual income – e.g. Between $60k – $90k

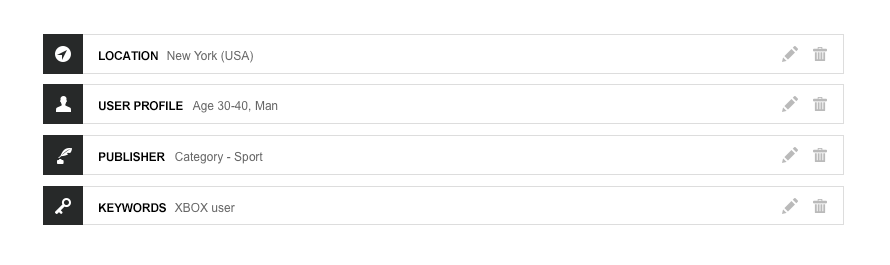

Advertisers can then combine multiple segments to directly target the audiences they want to reach with their online advertising campaigns.

Here’s an example of what that might look like:

Even though the segments help advertisers target their desired audience, they face a few problems:

Problem 1: Incorrect User Data

Generally, there is no way to tell how old the data is, and although some of the attributes don’t change often – gender, for instance – some may change every few months or even every few days (e.g. buying intents – if I decided to buy a sofa, I’m probably going to do that within next two weeks).

This change in consumer attributes can heavily affect the performance of an advertiser’s campaign, as even though they are targeting a desired audience, the ads displayed to the user could be completely irrelevant.

Problem 2: Attributing Revenue to the Right Supplier

It’s very common for profiles to appear in segments that have been created from multiple data sources, and a single segment could have been created from the data of hundreds of suppliers. Therefore, when the data is sold, the revenue (after the brokers’s commission) needs to be properly attributed to data suppliers and/or publishers proportionally to their contribution.

Unfortunately, there is no transparency on how this gets done and the attribution process cannot be verified. What’s worse is that there are currently more questions than solutions:

- Should the data broker (buyer) give a higher weight for the data’s newness?

- Should the quality of the data be taken into account?

- Should the amount of information that is given be taken into consideration and priced differently?

- How can suppliers and brokers resolve conflicts of the same data coming from multiple suppliers?

The truth is that there isn’t a simple solution to this problem.

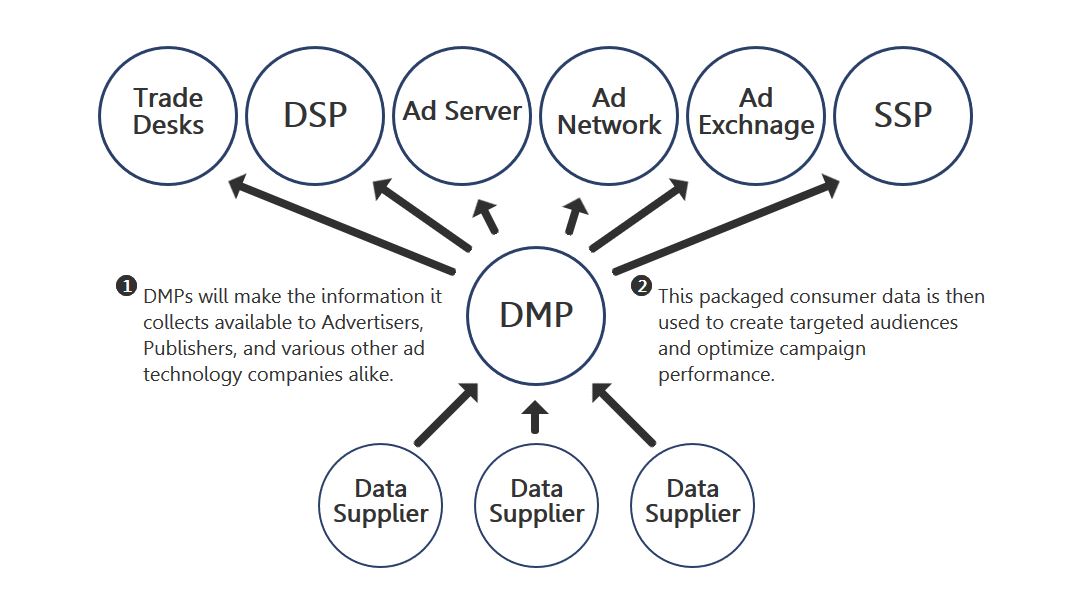

Selling Data to Other Parties

Apart from selling data directly to advertisers, brokers can also sell data to them through other technology platforms, such as demand-side platforms (DSP), ad exchanges, ad networks, supply-side platforms (SSP), and a few others. When the data is sold via a technology platform, it is sold on a CPM basis and billed on top of the purchased inventory (ad impressions).

This means that for every 1,000 impressions bought via a DSP in a campaign used for targeting data from the data broker, the advertiser will be billed an additional CPM price (e.g. $1) on top of the inventory they bought.

Once again, there are a few problems with this buying method.

Problem 1: Lack of Transparency

The main issue with this method of selling through technology platforms is that it’s incredibly non-transparent. Typically, it’s the DSP that reports to the DMP how much data was used during the real-time bidding (RTB) process, which makes it hard for the DMP to confirm exactly how much data was used.

The reason for that is in the RTB auction model, data is usually provided in every bid request sent to the DSP. The bidder on DSP side sends bids on behalf of the advertiser, but there is no way to tell if the bidder used the data during the exchange.

Problem 2: Static Pricing

The other problem with this model is that the price of the data is usually static. The only difference is that some segments are considered premium or of higher value than others, and the CPM price is then higher. There is no way to dynamically set the price for the data based on the demand and/or quality, and therefore, all the parties in the ecosystem (e.g. publishers, data suppliers, data brokers, advertisers, etc.) may be losing out financially.

An Overview of the Data Collecting and Trading System

The flow of user data through the online display advertising ecosystem is graphically explained in a presentation by displayadtech.com.

It’s also important to note that the data may be repackaged and resold from one DMP to another – just as long as their cookies are mapped.

Cookie Respawning

Cookies are currently, by far, the best and most popular method for tracking a user’s online activity on desktop devices. It’s therefore not surprising that most users who wish to remain anonymous, or at least limit the amount of companies tracking them online, delete and block third-party cookies. However, just because a user deletes cookies from their browser doesn’t mean they are gone forever.

Cookie respawning is a process whereby a cookie reappears, or respawns, after it has been deleted. It does this by using backed up data stored in additional files and then respawning later when a user accesses the site again.

The process looks like this:

- A user accesses a website.

- The website creates a cookie.

- The cookie tags the user’s browser with an unique identifier that is not easy to delete.

- The user leaves the website and deletes their cookies.

- The user accesses the website again and the (new) cookie recognises the identifier in the browser and respawns the original cookie.

Currently, there are two main methods for respawning cookies:

Flash cookies: Used by the browser plugin Adobe Flash Player to store information about the user on their computer. Most users are unaware of flash cookies and deleting them can only be done through the Adobe Flash Player settings.

HTML5: HTML5 local storage and cache cookies use entity tags (ETags) to respawn HTML cookies by recognizing the persistent identification element (PIE) created by JavaScript and Flash.

Who’s Tracking You?

From a user standpoint, the thought of one’s online data flowing through the web is often enough to make the most open person feel paranoid. Also, with the increase in third-party scripts and piggybacking, it can be very hard to identify which companies are tracking users, especially as this information is not easy to find and changes from site to site.

However, there are a few really great tools that can help people identify who is tracking their online movements.

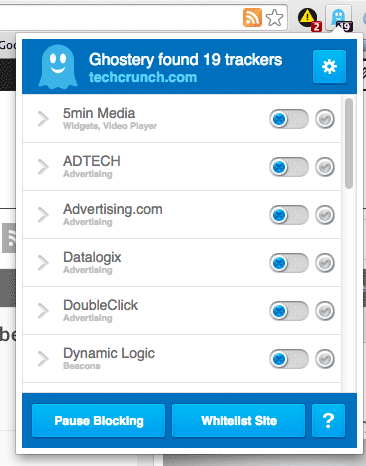

Ghostery

Ghostery is a browser add-on available on Firefox, Chrome, Safari, Internet Explorer, and Opera, as well as mobile (Android, iOS, Firefox android).

Once installed, a little ghost image with a number next to it will appear on the top right side of your browser’s toolbar. This number represents the trackers currently tracking you on the current web page.

Clicking on the ghost icon will reveal the name and types of trackers operating on that particular page.

Here’s the number and list of trackers showing up on the TechCrunch homepage:

Most trackers will be completely unknown to users, but there are a few that are well known, such as Facebook and DoubleClick (Google’s DSP), which will probably appear on most websites.

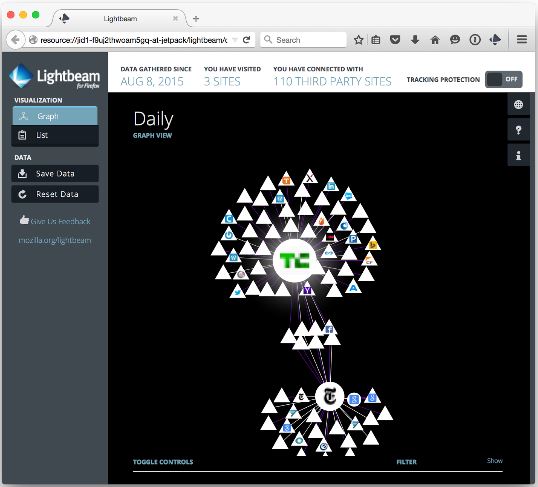

LightBeam

LightBeam is another great browser add-on for Firefox that lets you discover how many trackers are following your online movements.

Once installed, LightBeam will show you how many tracking requests were sent while you were visiting a website.

Visiting just two popular news sites (nytimes.com and techcrunch.com) resulted in 110 requests to third-party services, of which seven were called from both sites. You can see how it is visualized by LightBeam in the screenshot below:

Differing Views on Data Collection

There are many different views and opinions on the way users’ data is collected, shared, and sold online.

Some believe that if the tracking is only for advertising purposes, it poses no great risk to their privacy, while others believe that it is a clear violation of their privacy and will go out of their way to prevent companies from tracking their online movements.

Online privacy is a hot topic, especially since the NSA scandal broke in 2013, and with more and more users going online, the opportunities for companies to target them with their ads is only going to increase.

But regardless of your own view on data collection, it is an area of online display advertising that has many challenges to overcome – both from the business side and from the user side.

We Can Help You Build an AdTech Platform

Our AdTech development teams can work with you to design, build, and maintain a custom-built AdTech platform for any programmatic advertising channel.